When you see the words “loops” or “looping” in the context of coding, it refers to a specific type of flow control that allows the program to run the same lines of code many times.

Loops are a foundational part of almost all programming languages, and Python is no exception. It also allows programs to process immense amounts of data much faster than a human ever could. Thus, understanding loops is incredibly important for any non-trivial Python program. Examples of daily software tasks that use loops include reading and/or downloading data, serving a website, and producing graphics in a video game.

Chapter 3.3.1 - Loop Example: Reading image files¶

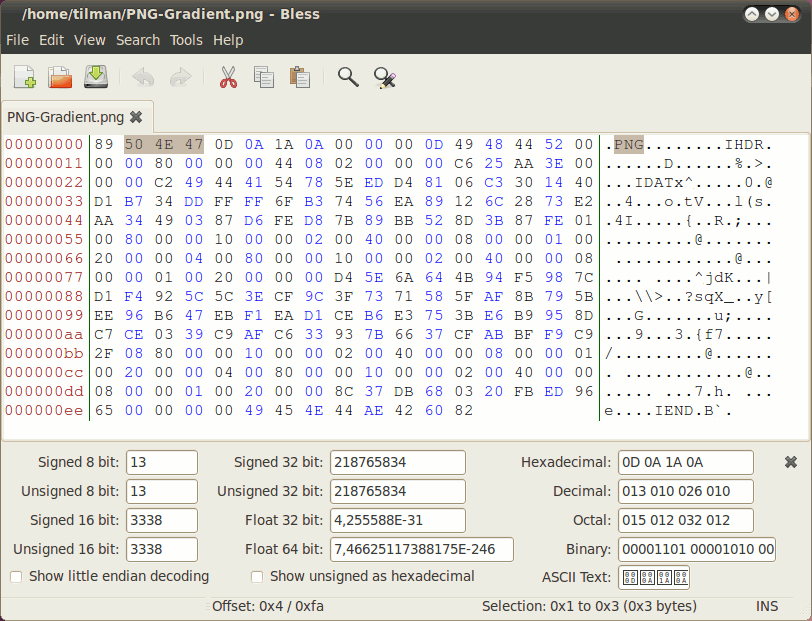

Data is often stored on your harddrive in a format that is not readable to humans if they were to visually inspect the data in a text editor.

For example, a “png” image of a cat might look like this:

A software package or web browser looks up the “specifications” of the file type (e.g. ‘png’) and then decodes the file into a representation that is interpretable by humans. The “psuedocode”, or “fake” code that describes the process without implementing the actual, working code, would look like this:

while not end of file

read line

if line data is a header

process header

elif line is image data

decode image data

add image data to a list

else

tell user there is an error

plot combined image dataIn other words, the “decoder” would read every one of the lines in the file and use “flags” (instructions) in the data to decide what to do inside an if/elif/else structure. It would continue to do this until it read a “end of file” flag, at which point, it would stop reading the file. During the loop, the results would be saved to a composite data type like a list. After the loop, the resulting data is then displayed as an image for the user.

Chapter 3.3.2 - Loop Example: Serving a website¶

Code running on a web server that “serves” a website is a form of an “event loop”. It continually checks for requests (events), and then executes code that can fulfill those requests. Depending on the scale of the server, it can check for requests many times a second. For example, the Amazon AWS system processes 400 million requests per second.

Psuedocode for a web server:

while the server is online

check for a request

if there is a request

read in the request code

if web page request

send the html and javascript needed for the browser to display the website

elif file request

send the requested file to the user

... (many other possible requests)

else

this request is not possible

else

check again

Chapter 3.3.3 - Loop Example: Running a video game¶

Video game code is similar to website code in that it also has an “event loop”. It continually checks for requests (events), and then executes code that can fulfill those requests. For example, a user may want to jump, and the code that displays the scene in the game must update the perspective of the 3D environment. Many games are “60 FPS”, which requires the loop to update the scene 60 times a second (or more). If the scenes are complex or the computer is not up to the task, you will notice a “lag” where the change in the perspective is not as smooth as it would be in “real life”. This could be due to complex scenarios (many characters or objects on the screen) or just normal variability in the GPU related to heat or background processes.

Psuedocode for a game server:

while the game is being played

check for user input

if there is a request

read in the request code

if move request

move in that direction using the speed input by the player

check if it hits wall, other player, ground, etc.

update the 3D position and central field of vision

update the perspective for pitch (up/down), roll (tilt), and yaw (side to side)

draw the graphics based on this new perspective

elif button request

if button is a:

throw rock animation

elif button is b:

move request to kneel down and pick something up

add item to inventory (list-like)

... (many other possible requests)

else

this request is not possible

else

check again

Chapter 3.3.4 - while loops¶

What you may have noticed in each case is that there is a pattern of “do something while something is true”.

The something is Python code, and “while something is true” is a condition. So we already know most of what we need for a while loop!

The typical control structure associated with a while loop is very similar to an if statement.

psuedocode:

while (condition is True):

#run code in a loop

#modify the condition so the loop eventually endsFor example, we could print all numbers between 1 and 10. What do we need to do?

Steps for creating a loop¶

Brainstorm: what would the output look like?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9Implement in a way you know: Create a basic solution in “regular” Python.

print(1)

print(2)

print(3)

print(4)

print(5)

print(6)

print(7)

print(8)

print(9)

print(10)1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Add complexity: how would you use only 1 variable?

a = 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a)1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Recognize the patterns: do you notice any repeating code? Try to identify the fewest lines that describe the step of printing a single number and then adding 1 to that number.

a = 1

print(a)

a = a + 11

So we know that the first step needs to print 1, so a should be set equal to 1 as an initialization step.

Next, we need to implement the while block. We can first create psuedocode to get an idea of what it might look like:

psuedocode (this is not meant to be runnable Python code)

set a equal to 1

while a is 10 or less

print a

add 1 to a

At this point, the only complexity is deciding on the condition. After the code below the while loop is executed, the condition is checked again. If it is False the loop is over, if it is True the code is run again.

The condition in this case would then be:

a <= 10which is True when a is equal to 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10

combining the condition with the psuedocode prototype gives us the following working Python code:

a = 1

while (a <= 10):

print(a)

a = a + 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

We can even print the test each step to see what happens. Since the last line in the while loop code is the last thing to happen before the condition is tested, we can place print(a <= 10) in the last line to simulate what the while loop does in the next step:

a = 1

while (a <= 10):

print(a)

a = a + 1

print(a <= 10)1

True

2

True

3

True

4

True

5

True

6

True

7

True

8

True

9

True

10

False

Notice that the first time (a <= 10) is False, no number is printed afterwards. The while loop was exited.

NOTE: Some of these examples will run forever, so you will need to press the stop sign above to stop the code from executing.

Chapter 3.3.5 - Common issues with while loops¶

1. Infinite loops

Infinite loops occur when the code that belongs to the while loop makes it impossible for the condition to ever be False. Thus, as the name suggests, the loop will continue on forever (or until you restart the kernel or press the stop button above). This is usually not desired behavior, and should be avoided. Always include a line of code that modifies variables associated with the condition in a way that eventually the test will “fail” (result in False).

There are a few ways that can result in an infinite loop. We will use the above example to illustrate. Please press the stop button above when you are convinced it is an infinite loop (the black square above the notebook). I suggest you press it multiple times immediately after pressing run or you will get 100s of lines of output. Python is running in that code block as long as there is a [*] instead of a [number].

You do not modify a variable within the test. If the test is True and nothing changes in the test, it will continue on forever. I am using

passas a placeholder for your code since you do not create 10s of thousands of lines of output and crash your computer. If the loop finishes, you should have printed out “Finished!” based on theprintstatement after thewhileloop block.

a = 1

while (a <= 10):

pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

print("Finished!")---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[6], line 5

1 a = 1

3 while (a <= 10):

----> 5 pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

7 print("Finished!")

KeyboardInterrupt: You do modify a variable within the test, but in a way in which the test will never be

False, so it will continue on forever.

a = 1

while (a <= 10):

pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

a = a - 1

print("Finished!")---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[7], line 7

3 while (a <= 10):

5 pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

----> 7 a = a - 1

9 print("Finished!")

KeyboardInterrupt: You modify a variable within the test as required, but the test is created in a way that it will never result in

False

a = 1

while (a >= 1):

pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

a = a + 1

print("Finished!")---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyboardInterrupt Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[8], line 3

1 a = 1

----> 3 while (a >= 1):

5 pass # placeholder for print(a) so we don't crash you computer

7 a = a + 1

KeyboardInterrupt: 2. Your while loop does not run because the condition is never True

You can have the opposite issue when you set up a while loop where the test is never True:

a = 1

while (a > 10):

print(a)

a = a + 1

print("Finished!")Finished!

3. Your while loop is almost right, but you are “one off”

This happens when you use the wrong test or initialization value.

Using the other example above, a small change to the test from (a <= 10) to (a < 10) will result in printing only 9 numbers:

a = 1

while (a < 10):

print(a)

a = a + 11

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

4. You modify your counter variable at the wrong time.

We know that code is run from top to bottom, and this is true within a while loop as well.

If you modify a in the previous example too early, this can result in undesired results!

a = 1

while (a < 10):

a = a + 1

print(a)2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Chapter 3.3.6 - Practice¶

Write a loop that loops until i is greater than 5. Set i initially to 0.

Write a loop that loops until i is greater than or equal to 5. Set i initially to 0.

Write a loop that loops until i is equal to 5

Write a loop that loops as long as i is not equal to 5

Write a while loop that loops while i is less than the length of the following list and then adds 1 to i at each step after starting at 0:

my_list = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]

Write a while loop that loops while i is less than the length of the following list, and then access the value at the index corresponding to the value of

iat each step and then adds 1 to i at each step after starting at 0:

my_list = [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]